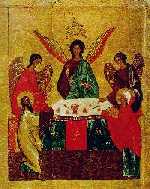

Andrei Rublev (ca 1360-1430) is the most famous Russian iconographer and his most famous work by far is his depiction of the Trinity. Art historian Alexander Boguslawski comments on some theological implications of this great icon.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Very few artists before Rublev

dared to eliminate all the narrative elements from the story, leaving

only the three angels; usually those who did so had to deal with

limited space. The results of their efforts did not find general

acceptance or many copyists. Rublev was the first to make a conscious

decision not to include in his composition the figures of Abraham and

Sarah because he did not set out to illustrate the story of the

hospitality of Abraham, as did many painters before him, but to convey

through his image the idea of the unity and indivisibility of the three

persons of the Trinity.

The doctrine of the Trinity,

difficult to explain logically, found various interpretations. Some

thought that the Trinity consisted of God the Father, God the Son, and

God the Holy Spirit. Others believed that it was just God and two

angels. In the 14th and 15th-century Russia, in the period of many

heretical movements, the idea of the Trinity was often questioned. The

heretics in Novgorod claimed that it is not permissible to paint the

Trinity on icons because Abraham did not see the Trinity but only God

and two angels. Other heretics rejected the idea of the three

hypostases of God altogether. The church fought the heresies with all

the means it had -- usually with polemical treaties, but also with

force, if necessary. Russian icon painters before Rublev subscribed to

the same point of view that Abraham was visited by God (in Christ's

image) and two angels. Hence, Christ was represented in icons of the

Trinity as the middle angel and was symbolically set apart either by a

halo with a cross, by a considerable enlargement of his figure, by

widely spread wings or by a scroll in His hand.

Trinity Icons. From left to right: Holy Trinity, a part of a quadripartite icon from Novgorod (first half of the 15th c.), Holy Trinity (Hospitality of Abraham), Novgorod School (middle of the 16th c.), Holy Trinity, Pskov School (15th c.).

In Rublev's icon for the first

time all the angels are equally important. Only this icon truly

conforms to the Orthodox idea of the Trinity. But Rublev's genius

allows the painter to go beyond the constraints of theological theme.

His icon is a special kind of challenge to the antitrinitarians --

instead of forcing them to accept the dogma, Rublev softly and gently

tries to bring them to the dogmatic understanding of the icon's meaning.

All scholars agree that the three

hypostases of the Trinity are represented in Rublev's icon. But there

are greatly differing views as to which angel represents which

hypostasis. Many see Christ in the middle angel and God the Father in

the left. Others see God the Father in the middle angel, and Christ in

the left one. The middle angel occupies a special place in the icon:

it is set apart not only by its central position, but also by a "regal"

turn of its head towards the left angel, and by pointing with its hand

towards the cup on the table. Both the turn of the head and the gesture

are important clues to the hidden meaning of the icon. Equal among

equals, the middle angel has such expressive power that one hesitates

not to see in it a symbolic representation of God the Father. On the

other hand one cannot fail to notice that the left angel is also

essential: two other angels lower their heads towards it and seem to

address it. Therefore, if we assume that the left angel is God the

Father, the middle angel, dressed in the clothes customarily used in

compositions depicting the second person of the Trinity (a blue

himation and a crimson tunic), should represent Christ. This

amazing and perhaps purposeful encoding of these two persons of the

Trinity by Rublev does not give us a clear clue for a single

interpretation. Whatever the case, the icon shows a dialogue between

two angels: The Father turns to His Son and explains the necessity of

His sacrifice, and the Son answers by agreeing with His Father's wish.

Neither of these interpretations

impacts the interpretation of the Trinity as triune God and as a

representation of the sacrament of the Eucharist. The cup on the table

is an eucharistic symbol. In the cup we see the head of the calf which

Abraham used for the feast. The church interprets this calf as a

prototype of the New Testament Lamb, and thus the cup acquires its

Eucharistic meaning. The left and the middle angels bless the cup: The

Father blesses His Son on his Deed, on His death on the cross for the

sake of man's salvation, and the Son, blessing the cup, expresses his

readiness to sacrifice Himself. The third angel does not bless the cup

and does not participate in the conversation, but is present as a

Comforter, the undying, a symbol of eternal youth and the upcoming

Resurrection.