The French Orthodox theologian Olivier Clement (1921-2009) in his The Roots of Christian Mysticism (New City Press 1993) succinctly ties together the Eastern Christian concepts of divine essence, divine energies, and the process of theosis or divinization. The quote is found on pp 237-238.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

The Fathers distinguish here, without in any way separating them, the inaccessible essence of God and the energy (or energies) by means of which his essence is made inexhaustibly capable of being shared in. It is a distinction that is inherent in the reality of the divine Persons and it points, on the one hand, to their secret nature and, on the other hand, to the communication of their love and their life. The essence does not imply a depth greater than the Trinity; it means the depth in the Trinity, the depth that cannot be objectivized, of personal existence in communion. The inaccessibility of the essence means that God reveals himself of his own free will by grace, by a "folly of love" (St Maximus's expression). God in his nearness remains transcendent. He is hidden, not as if in forbidden darkness, but by the very intensity of his light. It is only God's inaccessibility that allows the positive space for the development of love through which communion is renewed. God overcomes otherness in himself without dissolving it and that is the mystery of the Trinity in Unity. He overcomes it in his relations with us, again without dissolving it, and that is the distinction-identity of the reality and the energies. "God is altogether shared and altogether unshareable", as Dionysius the Aeropagite and Maximus the Confessor say. The energy is the expansion of the Trinitarian love. It associates us with the perichoresis of the divine Persons.

God as inaccessible essence--transcendent, always beyond our reach.

God as energy capable of being shared in--God incarnate, crucified, descended into hell, risen from the dead and raising us up, that is, enabling us to share in his life, even from the starting point of our own enclosed hell--God always within our reach.

The energy--or energies--can therefore be considered from two complementary standpoints. On the one hand is life, glory, the numberless divine Names that radiate eternally from the essence. From all eternity God lives and reigns in glory. And the waves of his power permeate the universe from the moment of its creation, bestowing on it its translucent beauty, masked partially by the fall. At the same time, however, the energy or energies that create and maintain the universe, and then enable it to enter potentially into the realm of the Spirit, and to be offered the risen life. All these operations therefore are summed up in Jesus, the name that means "God saves", "God frees", "God sets at liberty". In his person humanity and all creation are "authenticated", "spiritulalized", "vivified", since, as St Paul saves, "in him [Christ] the whole fullness of deity dwells bodily" (Col 2: 9). The energy as divine activity ensures our share in the energy as divine life, since what God gives us is himself. The energy is not an impersonal emanation nor is it a part of God. It is that life that comes from the Father through the Son in the Holy Spirit. It is that life that flows from the whole being of Jesus, from his pierced side, from his empty tomb. It is that power that is God giving himself entirely while remaining entirely above and beyond creatures.

Jeremy Taylor (1613-1667) lived during one of the most crucial periods in Anglican history. Educated at Oxford, he enjoyed the patronage of Archbishop Laud, who gave him a fellowship at All Souls College as well as an appointment as royal chaplain. As can be imagined, these royalist ties did him little good when Cromwell came to power, and after several stints in jail he spent most of the years of the Protectorate in semi-seclusion, as tutor to the children of a Welsh nobleman. He took advantage of this time to produce most of his theological writings, which assure him a place within the pantheon of the "Caroline Divines". His fortunes took an upswing with the restoration of Charles II, who named him bishop of Down, Connor, and Dromore in Ireland, as well as chancellor of Trinity College, Dublin. Neither of these positions was a sinecure, since the college was in very poor shape and a number of his clergy had presbyterian sympathies, lacked episcopal ordination, and saw no reason why they should seek it from him.

Taylor's output was voluminous and he wrote on a wide range of topics. For his feastday I choose some of his thoughts on the Eucharist, taken from his 1653 book The Great Exemplar. It can be found in the very useful Anglican Eucharistic Theology website. Note references to "partaking in the Divine nature", analogous to the Eastern Christian concept of theosis.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

[Christ's] power is manifest, in making the symbols to be the the instruments of conveying himself to the spirit of the receiver: he nourishes the soul with bread, and heals the body with a sacrament; he makes the body spiritual, by his graces there ministered, and makes the spirit to be united to his body, by a participation of the Divine nature. In the sacrament, that body which is reigning in heaven is exposed upon the table of blessing; and his body, which was broken for us, is now broke again, and yet remains impassible. Every consecrated portion of bread and wine does exhibit Christ entirely to the faithful receiver; and yet Christ remains one, while he is wholly ministered in ten thousand portions...God hath instituted the rite in visible symbols to make the secret grace as presential and discernable as it might; that by an instrument of sense, our spirits might be accomodated,as with an exterior object, to produce an internal act...Our wisest Master hath appointed bread and wine, that we may be corporally united to him; that as the symbols, becoming nutriment, are turned into the substance of our bodies; so Christ, being the food of our souls, should assimilate us, making us partakers of the Divine nature.

Taylor's output was voluminous and he wrote on a wide range of topics. For his feastday I choose some of his thoughts on the Eucharist, taken from his 1653 book The Great Exemplar. It can be found in the very useful Anglican Eucharistic Theology website. Note references to "partaking in the Divine nature", analogous to the Eastern Christian concept of theosis.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

[Christ's] power is manifest, in making the symbols to be the the instruments of conveying himself to the spirit of the receiver: he nourishes the soul with bread, and heals the body with a sacrament; he makes the body spiritual, by his graces there ministered, and makes the spirit to be united to his body, by a participation of the Divine nature. In the sacrament, that body which is reigning in heaven is exposed upon the table of blessing; and his body, which was broken for us, is now broke again, and yet remains impassible. Every consecrated portion of bread and wine does exhibit Christ entirely to the faithful receiver; and yet Christ remains one, while he is wholly ministered in ten thousand portions...God hath instituted the rite in visible symbols to make the secret grace as presential and discernable as it might; that by an instrument of sense, our spirits might be accomodated,as with an exterior object, to produce an internal act...Our wisest Master hath appointed bread and wine, that we may be corporally united to him; that as the symbols, becoming nutriment, are turned into the substance of our bodies; so Christ, being the food of our souls, should assimilate us, making us partakers of the Divine nature.

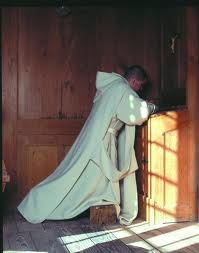

In western Christianity the Carthusian monastic order best maintains the lifestyle of the original Desert Fathers. The monks live as hermits in strictly enclosed "charterhouses" with no outside ministries, spending most of their time in their cells engaged in meditation and personal prayer.

The order was founded in 1084 by St Bruno of Cologne, and survives today in 25 charterhouses sheltering about 350 monastics, including nuns. It has largely adhered to its original rule, despite the extreme rigor of the Carthusian life--only about 10 percent of the monks die in vows. There is a small body of Carthusian writing, usually anonymous. a sample of this is found in The Wound of Love: a Carthusian miscellany (Cistercian Publications 1994). A sermon on today's feast of the Transfiguration, excerpted below, is found on pp 35-39.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

In the Transfiguration, we are dealing with exceptional prayer. The Spirit of the Lord is upon Jesus. As at his baptism, he must enter into a solemn moment of his return to the Father. The Transfiguration is a pinnacle of his existence, yet it is much more a point of departure. Jesus enters thus into the mystery of his 'exodus', as St Luke says in reference to the conversation between the Saviour and Moses and Elijah. The Paschal Mystery is already beginning and is played out in light, just as in Gethsemane it will be played out in darkness. Jesus is at the summit of a new Horeb, flooded by the Spirit; he is in the process of concluding the new alliance which will soon be sealed in his blood. The light in which he is bathed reveals his full right of access to the Father. It inaugurates already his entrance into glory.

However, this meeting of the humanity of the Son with the Father does not take the form of a crushing presence on the part of an impersonal God. It appears rather as communion with Moses and Elijah. His two predecessors on the holy mountain are there to welcome him and to show that the New Covenant is a work of love. There is not only the communion of the Father and the Son in the Spirit; there is its permanent and visible sign: the encounter between human beings of flesh and blood, who, when transformed by light, continue to possess a heart that thirsts to give itself.

[The apostles] are to become sharers in the glory which suffuses Jesus. What occurred in the depths of his soul is made known to them by the Father's voice. He reveals once again that Jesus is his Son, the Beloved, the Chosen One of whom the prophets spoke. The occasions on which the Father himself proclaims his intimacy with the Son in the Spirit so directly are extremely rare in the Gospel. The baptism of Jesus was the first time; Peter at Caesarea Philippi had spoken in the same way under the direct inspiration of the Father; now today, on the mountain top, the Father again intervenes to make the disciples penetrate more profoundly into the mystery of the Son, the Son who enters into the Paschal Mystery so as to return to his Father.

From now on, the disciples will be bearers of a momentous secret. They had followed Jesus into a mountain solitude in order to pray near him; now they are introduced into a solitude still greater: the solitude of mystery. They were told by the Father to listen to Jesus, but he has nothing to say to them for the moment other than to keep quiet. Solitude in the company of Jesus has introduced them to silence.

The order was founded in 1084 by St Bruno of Cologne, and survives today in 25 charterhouses sheltering about 350 monastics, including nuns. It has largely adhered to its original rule, despite the extreme rigor of the Carthusian life--only about 10 percent of the monks die in vows. There is a small body of Carthusian writing, usually anonymous. a sample of this is found in The Wound of Love: a Carthusian miscellany (Cistercian Publications 1994). A sermon on today's feast of the Transfiguration, excerpted below, is found on pp 35-39.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

In the Transfiguration, we are dealing with exceptional prayer. The Spirit of the Lord is upon Jesus. As at his baptism, he must enter into a solemn moment of his return to the Father. The Transfiguration is a pinnacle of his existence, yet it is much more a point of departure. Jesus enters thus into the mystery of his 'exodus', as St Luke says in reference to the conversation between the Saviour and Moses and Elijah. The Paschal Mystery is already beginning and is played out in light, just as in Gethsemane it will be played out in darkness. Jesus is at the summit of a new Horeb, flooded by the Spirit; he is in the process of concluding the new alliance which will soon be sealed in his blood. The light in which he is bathed reveals his full right of access to the Father. It inaugurates already his entrance into glory.

However, this meeting of the humanity of the Son with the Father does not take the form of a crushing presence on the part of an impersonal God. It appears rather as communion with Moses and Elijah. His two predecessors on the holy mountain are there to welcome him and to show that the New Covenant is a work of love. There is not only the communion of the Father and the Son in the Spirit; there is its permanent and visible sign: the encounter between human beings of flesh and blood, who, when transformed by light, continue to possess a heart that thirsts to give itself.

[The apostles] are to become sharers in the glory which suffuses Jesus. What occurred in the depths of his soul is made known to them by the Father's voice. He reveals once again that Jesus is his Son, the Beloved, the Chosen One of whom the prophets spoke. The occasions on which the Father himself proclaims his intimacy with the Son in the Spirit so directly are extremely rare in the Gospel. The baptism of Jesus was the first time; Peter at Caesarea Philippi had spoken in the same way under the direct inspiration of the Father; now today, on the mountain top, the Father again intervenes to make the disciples penetrate more profoundly into the mystery of the Son, the Son who enters into the Paschal Mystery so as to return to his Father.

From now on, the disciples will be bearers of a momentous secret. They had followed Jesus into a mountain solitude in order to pray near him; now they are introduced into a solitude still greater: the solitude of mystery. They were told by the Father to listen to Jesus, but he has nothing to say to them for the moment other than to keep quiet. Solitude in the company of Jesus has introduced them to silence.

Christ of Hagia Sophia

Contributors

- Joe Rawls

- I'm an Anglican layperson with a great fondness for contemplative prayer and coffeehouses. My spirituality is shaped by Benedictine monasticism, high-church Anglicanism, and the hesychast tradition of Eastern Orthodoxy. I've been married to my wife Nancy for 38 years.

Archives

Categories

- theosis

- eucharist

- Resurrection

- Benedictines

- Judaism

- Trinity

- liturgy

- Anglicanism

- Christmas

- Transfiguration

- baptism

- monasticism

- Andrewes

- Ascension

- Irenaeus

- Jesus Prayer

- Kallistos Ware

- Rowan Williams

- creed

- icons

- universalism

- Book of Common Prayer

- Climacus

- Easter

- Merton

- Rublev

- Teresa of Avila

- Underhill

- desert fathers

- incarnation

- mysticism

- repentance

- science

- Aquinas

- Athanasius

- Athos

- Cabasilas

- Clement

- Daily Office

- Gregory the Great

- Isaac of Nineveh

- Jesus seminar

- Julian

- Lossky

- Luther

- Pachomius

- Pentecost

- Ramsey

- Rule

- Wright

- angels

- christology

- ecology

- eschatology

- evangelicals

- hesychasm

- kenosis

- lectio divina

- litany

- nativity

Nicholas Ferrar

Older Posts

- "A Great Understanding"

- A Jew on the Resurrection

- A Wild and Crazy God

- Advent Repentance

- All Saints

- Amen, Brother, and Pax Vobiscum!

- Anglican Hermits in the Big Apple

- Anglican Theology: Follow the Bouncing Balls

- Anglican Values

- Anglo-Catholic Identity

- Animal Saints

- Anthony Bloom on the Transfiguration

- Ascension and the Sanctification of Matter

- Ascesis and Theosis

- Athanasius on the Trinity

- Athonite Benedictines

- Augustine on the Ascension

- Authentic Mysticism

- Baptism and Kenosis

- Bede on the Transfiguration

- Begging for Mercy in the Jesus Prayer

- Being About My Father's Busy-ness

- Benedict and the East

- Benedict on Humility in Christ

- Benedictine Stability

- Bishop Andrewes' Chapel

- Bishop Hilarion on Prayer and Silence

- Blessed John Henry Newman

- Booknote: In the Heat of the Desert

- Booknote: Short Trip to the Edge

- Booknote: The Essential Writings of Christian Mysticism

- Booknote: The Uncreated Light

- Boredom Eternal?

- Born-again Sacramentalism

- Bulgakov on the Incarnation

- Camaldoli's Eastern Roots

- Chalcedon and the Real World

- Chittister on Benedictine Prayer

- Christmas Foreshadows Easter

- Clairvaux Quotes

- Climacus Condensed

- Cloister of the Heart

- Colliander on the Jesus Prayer

- Communion After Baptism

- Communion Prayers

- Creeping Up the Ladder

- Daily Readings from the Rule of Benedict

- Darwin and the Rabbi

- Dueling Worldviews

- Ephrem the Syrian

- Esoteric and Exoteric

- Essence, Energies, Theosis

- Eucharist and Creed

- Eucharist and Ecology

- Eucharistic Quotes: Anglican

- Eucharistic Quotes: Patristic

- Eucharistic Quotes: Roman Catholic

- Evagrius on Prayer

- Exaltation of the Holy Cross

- George Herbert

- Getting Our Priorities Straight

- God in Creation

- Great O Antiphons

- Gregory of Nazianzus on Baptism

- Gregory on Michael

- Gregory the Great on Angels

- Healing Words

- Heschel on Prayer

- Hildegard on the Trinity

- Holy Fear(s)

- Incarnation and Theosis

- Irenaeus and the Atonement

- Irenaeus on Pentecost

- Irenaeus on the Trinity

- Jewish Figures in the Eastern Liturgy

- John Donne

- John of the Cross

- Julian and the Motherhood of God

- Kallistos Ware on the Jesus Prayer

- Lancelot Andrewes on the Resurrection

- Lancelot Andrewes on Theosis and Eucharist

- Latin Strikes Back

- Lectio Divina Resources

- Liber Precum Publicarum

- Litany of St Benedict

- Living in the Present Moment

- Lossky on the Transfiguration

- Luther and Theosis

- Marilyn Adams on the Resurrection

- Merton and Sophia

- Monk-animals

- Monks on Silence

- Monks, in a Nutshell

- Monstrance as Mandala

- Moralistic Therapeutic Deism

- More on Green Orthodoxy

- Myrrh-bearing Witnesses

- Mystical Tofu

- Newark's mea culpa

- Nicholas Ferrar

- No Free Passes for Skeptics

- Of Limited Pastoral Use

- Old Rites, Young Bodies

- Olivier Clement on the Eucharist

- Orthodox Thought Control

- Pachomius

- Papal Fashion Statements

- Paschal Proclamation

- Passover and Eucharist

- Patriarch's Paschal Proclamation

- Poetry by Herbert

- Polkinghorne on Creationism

- Polkinghorne on the Resurrection

- Prayers to St Benedict

- Praying With the Trinity Icon

- Priorities

- Ramsey on Anglican Theology

- RB and BCP

- Recovering Secularists

- Reinventing the Monastic Wheel

- Rescuing Darwin

- Resurrection in Judaism and Christianity

- Roman Christmas Proclamation

- Rowan on Wisdom, Science, and Faith

- Rowan Williams on Teresa of Avila

- Rowan Williams on the Resurrection

- Rublev's Circle of Love

- Rublev's Sacred Geometry

- Salvation for All Revisited

- Salvation for Everyone?

- Seraphim of Sarov

- Seven Lenten Theses

- Shell Games

- Sinai Pantocrator

- Spiritual and Religious

- St Benedict the Bridge Builder

- St Ignatius Brianchaninov on the Jesus Prayer

- St John Cassian on Prayer

- St John of Damascus

- St Joseph's Womb

- St Padraig's Creed

- Sweetman on Faith and Reason

- Symeon on the Eucharist

- Sympathy for the Devil?

- Teresa of Avila

- The Anglican Great Litany

- The Dormition of the Theotokos...

- The Green Patriarch

- The Jesus Prayer

- The Mystery of Holy Saturday

- The Resurrection is Not a Bludgeon

- Theology Isn't a Head Trip

- Theology Lite?

- Theosis and Eucharist

- Theosis and the Name of Jesus

- Theosis for Everyone

- Theosis in the Catholic Catechism

- Theosis: What it's all about

- Thomas Merton on the Jesus Prayer

- Three Faces of CS Lewis

- Transfiguration and Suffering

- Transfiguration Quotes

- Trinitarian Dance

- Two Sides of the Same Coin

- Underhill on Theosis

- Underhill on Worship

- Victory in Christ

- Virgin of the Sign

- What's Really Important?

- Why the Creed Matters

- Wright on the Resurrection

- Young Geezers and the Liturgy

- Zizioulas on Baptism and Eucharist

Lancelot Andrewes

Anglicans

- A Desert Father

- A Red State Mystic

- Affirming Catholicism

- All Things Necessary

- Anglican Communion

- Anglican Eucharistic Theology

- Anglican Society for the Welfare of Animals

- Anglo-Orthodoxy

- Catholicity and Covenant

- Celtic-Orthodox Connections

- Chantblog

- Chicago Consultation

- Creedal Christian

- Don't Shoot the Prophet

- Episcopal Cafe

- Episcopal News Service

- Evelyn Underhill

- Faith in the 21st Century

- For All the Saints

- In a Godward Direction

- Inclusive Orthodoxy

- Interrupting the Silence

- Into the Expectation

- N. T. Wright

- Nicholas Ferrar and Little Gidding

- Preces Privatae

- Project Canterbury

- Society for Eastern Rite Anglicanism

- Society of Catholic Priests

- St Bede's Breviary

- Taize Community

- The Anglo-Catholic Vision

- The Benedictine Spirit in Anglicanism

- The Conciliar Anglican

- The Daily Office

- The Hackney Hub

- The Jesus Prayer (Anglican perspectives)

- The St Bede Blog

- Thinking Anglicans

St Benedict Giving the Rule

St Gregory Palamas

Eastern Christians

- A Spoken Silence

- A Vow of Conversation

- Ancient Christian Defense

- Ancient Faith Radio

- Antiochian Orthodox Church

- Coptic Church

- East Meets East

- Eclectic Orthodoxy

- Ecumenical Patriarchate

- Glory to God for All Things

- Hesychasm

- Jewish Roots of Eastern Christian Mysticism

- Malankara Syriac Church

- Mar Thoma Syrian Church of Malabar

- Monachos

- Mount Athos

- Mystagogy

- Nestorian Church

- Occidentalis

- Orthodox Arts Journal

- Orthodox Links

- Orthodox Peace Fellowship

- Orthodox Way of Life

- Orthodox Western Rite

- OrthodoxWiki

- Pravoslavie

- Public Orthodoxy

- Salt of the Earth

- The Jesus Prayer

St Gregory the Great